Episode #10: Does Humanity Evolve?

Collaborative Art For The Common Good

John Quigley is an aerial artist and activist whose iconic work has been the face of many issues across health, human rights, social justice, environment, democracy, and freedom. His unique mix of human installation, aerial photography, and political activism brings together communities to create large-scale messages for the common good. Turtle Talks creator and host Monica Laurence sits down with John to discuss how his work strives to liberate the spirit and inspire unity and creative activation through participation.

VIEW FULL TRANSCRIPT BELOW

Monica: This is Monica Laurence. I’m here with aerial artist, producer and activist, John Quigley. John has created human aerial art images around the world and on every continent. His art addresses themes of ecology, health, human rights, social justice, democracy and freedom. John’s vision is to liberate the human spirit and inspire unity through creative participation. John, thank you for joining us on Turtle Talks.

John: Thank you so much, Monica.

Monica: So what is aerial art?

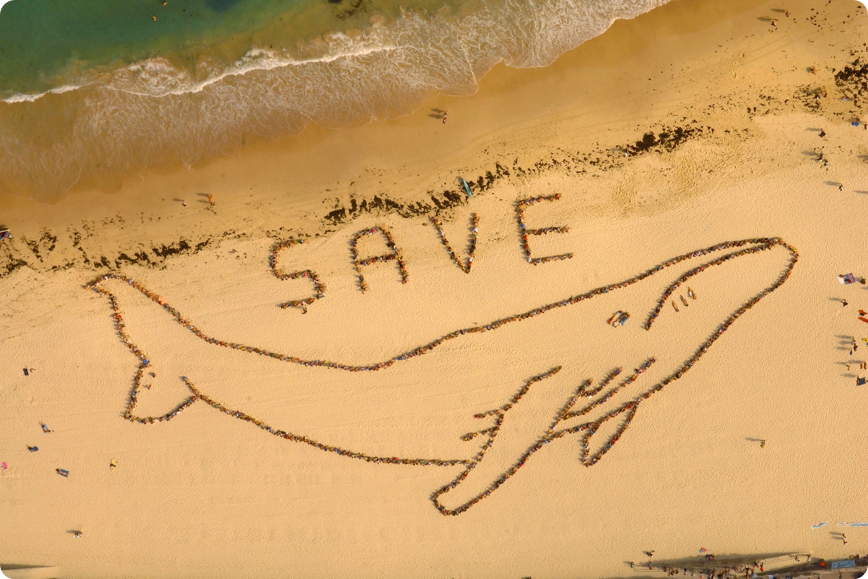

John: Well, aerial art is the creation of forms upon the land that can only truly be seen from the sky. It’s a term that I coined 15-20 years ago. I do it with people the vast majority of the time, where we take large crowds and create giant images with their bodies for social and environmental issues. Often times in our world there are very few forms that people can communicate what matters to them that haven’t been co-opted by the corporate sales machine. And I found with this medium that it was respected by mainstream media because of the precision that was required and that we were able to really amplify the voices of people all over the world on issues that were, in many, many cases, life and death issues for them.

Monica: Can you give us an example of one of these experiences? Of perhaps even a life and death issue?

John: Virtually every time I’ve worked in the Amazon it’s a life and death issue in that you have indigenous tribes that are fighting resource extraction that threaten the landscape itself through oil spills and other toxic situations, but also the death of their culture. So at one point, it was really challenging for me because I realized that pretty much everything I was doing, I was working with people who are right on the brink. And to steep yourself in that kind of information every day over a long period of time it’s challenging to keep your positivity going. I think that’s the most important tool that we have as advocates and activists and artists is to be able to hold this vision of what’s possible.

When you’re with people who are being pushed to the brink of their very existence culturally and in many cases physically, holding on to that vision of what’s possible is really key when people come together there’s this sort of super energy that occurs when people are aligning and they’re creatively activating together. That generates hope, it generates possibility, it generates a strength that a group can hold, that it’s much more difficult for a single individual to hold.

Monica: What was the project that you did in the Amazon?

John: I’ve done several in the Amazon. There’s an area the size of Rhode Island in Northern Ecuador where there isn’t a single drop of clean water. It’s because of a thousand un-lined oil pits that were left behind by Chevron Texaco. It’s called the Rainforest Chernobyl, and it’s been over 20 years, a court case against Chevron for having poisoned a huge area of the Amazon.

In 2007 we went to the site. There’s this very strange museum actually. The first oil well drilled in Northern Ecuador has been memorialized as this tourist attraction. It’s called Texaco Uno back when it was Texaco, and it’s the oil rig that… it was the first puncture wound, that’s how I look at it, the first puncture wound in the Amazon in Northern Ecuador which led to the worst oil disaster in world history.

So we went and occupied the site with 700 indigenous tribes and campesinos, and created an image there that just said “¡Justicia ya!”and it was… I climbed up the oil rig with one of the Cofan leaders in his full headdress. There we are on top of this oil rig, directing the crowd into this giant image of “Justice now!” while the helicopters were filming from above. And then the following week I travelled 14 hours east into near the border with Peru in Ecuador to a place called the Yasuni which is the most biologically diverse area of the entire Amazon. They call it the “Cradle of Life”. It’s one of the few places that didn’t freeze during the Ice Age, and the theory is that a lot of the Amazon basin was repopulated after the Ice Age ended from the Yasuni, from the Cradle of Life. Now, it also happens to be the area of the largest oil reserves in Ecuador under the ground.

At the time, we were fortunate because of the disaster in the north; the government was really working to protect the Yasuni. We actually took the photograph from the Vice Presidential helicopter that we did in this little clearing near one of the ranger stations in the Yasuni. One of the most beautiful things about Yasuni is I had spent a few days at a rainforest lodge in another part of Ecuador — exquisite amazing experience — but as we were traveling up the river to Yasuni, you started to see the diversity really blossom to the point that when we got to the Yasuni, the colors, the vibrancy of the flower petals was at a completely different level from what I would already have called paradise. So you really noticed how special this place was.

The Vice President, at the time, of Ecuador, was in a wheelchair so he was actually carried by some of his aides through the jungle to be part of this image that was a very simple message but it said “Vive Yasuni”, and in English “Live Yasuni”. And so a combination of those bookends from the worst of the worst to the best of the best in the Amazon, that was a very striking thing. That was all packaged into a video that was broadcast. It was narrated by Martin Sheen in addition to getting media in Ecuador which at the time was really crucial because Chevron was taking out a lot of ads that there was no way the people we were working with could compete economically with, so instead the image “¡Justicia Ya!” was on the front page of all the newspapers. Our way of rebutting their propaganda was to have the people actually go and send this message with their bodies. So that’s part of the power of the messaging.

It’s a communications tool but also a way to engender spirit and camaraderie and unity amongst those who participate. Unfortunately about a year ago I got a call saying that they’re going after the Yasuni again. Someone once said there are no permanent environmental victories, so we rallied to put together a video with a lot of top international celebrities advocating for the continued protection of the Yasuni. So one of the great victories that I’ve been involved with, seven years later we were fighting it all over again.

So it’s this constant push, this constant spark. I like to call it the spark, the spark of consciousness, the spark of possibility. We just carry it while we’re here, while we’re alive, and it’s so important to spread it as far and wide as we can because then others can carry it, and then we don’t feel like we have to carry it all.

I think what happens with this art form is that in a moment you bring together all of these people and that spark gets ignited in a bigger way and they all then go back to their families, their villages, their cities, and they become the source of the spark for other people. And as long as that spark is alive, there is possibility. So many times I look around at the way the world is working now, it almost feels like there’s this conspiracy to douse the spark. And so those of us who feel it, that’s all you’ve got to do is keep it alive.

One other story related to that is I was at a gathering of activists, activists that I deeply respect. And we did an exercise of imagining 25 years in the future; an Amazon that had been restored and was thriving. And some of the most amazing activists that I know, who are working on this issue right now, they were having a hard time doing that. And I was in shock. But as we talked about it, I realized they’re so in the day-to-day of dealing with the repressive policies of governments, of corporations, that they were losing their ability to hold the vision of what was possible.

As advocates for the future, that is job one. Job one is protecting and nurturing that part of ourselves that can truly imagine the world that we want to see. Without that, it will not become reality. With that, we have an incredible opportunity for other forces unseen, unknown to us to come to our aid to make that a reality. So holding that vision of the world we want to see, that other world that’s possible, is absolutely the fundamental bedrock of what it is to advocate for the future we want.

And then from there you can take all of the tangible actions necessary to manifest that world. I think in many ways the art work that I do, in addition to being a communications tool for an issue and a uniter for a community or even a group of people who don’t normally work together, it’s a mind shift about what’s possible. If this on one day in one moment is possible for us all to become part of this thing that’s larger than ourselves, then maybe some of these visions that seem so daunting are also possible. I guess, for me, I attempt to just continually spark possibility in the world and to enroll more and more people into feeling that they can do that as well.

Monica: That’s amazing. Love it. Okay. John, you must have requests and opportunities from many different projects. How do you decide where you want to invest your time?

John: It’s a combination of things. There’s this sort of inner voice, this inner sonar which is about what are the greatest points of need, and what are in combination with what are the leverage points for change. So I did a project… I mean sometimes it comes in the middle of the night where there’s just a vision that happens. I did a project last year on the Keystone pipeline route in Nebraska where I literally woke up at 3:00 in the morning just going, “I have to go to the pipeline route and create a giant image.” And I had been thinking about it for a while but I didn’t know how I could possibly get people to such a remote area. I woke up and it was like I had electricity in my hands and I couldn’t sleep and the next morning I made a couple phone calls and immediately someone said, “Where have you been? We’ve been wanting to do this for five years. We didn’t have the expertise. I have the perfect farm for you to do it in.” And so I ended up creating the world’s largest crop art 28 days later on the pipeline route that also was the intersection point with the Ponca Trail of Tears.

That was the situation. If you put it on a spectrum that was just pure what I would call divine inspiration on one hand that then manifests very quickly. Sometimes people, they’ll reach out, they’ll tell me their story and I’ll just want to help them. Generally what I do at least gives them attention in the media and ways for them to continue to build their movement around whatever issue. It’s usually something that resonates with me as “This is important in this time frame. This is the moment for this now.” And it’s almost always, there’s a little bit of analysis but a lot of it is intuitive. And also I assess capacity because people get very excited about this work but to gather together a large crowd and to make it all work requires a certain level of scale, of production. I will take people through that process of do they have the capacity to help make that happen. And then if it’s in the relative range and I feel really passionate about it, I’ll just go for it.

Monica: How would you describe your values, your principles around which you are passionate?

John: That’s interesting. I thought about this the other day. Basically, I’m a combination of my parents’ Depression Era/World War II values of basic human decency combined with “We’re all on the same team” and then heavily influenced by The Beatles and John Lennon and the whole “What’s possible, imagine the world that you want to see”. So it’s a combination of those two things.

I think I’m a representative of that idea. The basic thesis of my artwork is that everyone’s an artist and that everyone’s life is a work of art. My mum used to talk about sculpting life, just sculpting life, like shaping life as you go along and that we’re all winging it. I mean we’re all dealing with our families, life and death, these transitions, these rights of passages, the pressures of how do we bring in resources. We’re all having the same experience but so often we forget and we start dividing each other by labels. Just getting things… so for me the work is about, literally when you look at the photo at the end of one of these projects it couldn’t have happened without every single dot. And that dot represents a life, a dream, an aspiration, a family, a community, a whole world onto itself.

But then when you put it together, it’s a giant Picasso or you put it together and it’s a giant eagle flying over the heartland of America protecting water. And so we need to find ways to access our own creativity and our own sense of possibility that is beyond the rational because the rational is an amazing tool to a point but it can also become our prison.

Many times doing these projects I talk about we’re breaking up the monolith and we’re creating this sort of vertical communication. We’re bellowing to the sky our dreams and aspirations, and in the process there’s some chaos that occurs. And that chaos helps to break up the monolith of our thinking, of our rigid structures in the brain and all of that, and that requires a certain leap of faith. For some people who want everything to be by the book, it’s not a Disneyland ride where every emotion is pre-programmed and all of that.

I get into situations where I have people on landscapes in 30 degrees below 0 or on frozen tundra that’s half melted in puddles of water like working up in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge and with the Gwich’in people and I was like, “Okay, now I want everyone to get on the ground.” And they looked around and it was like frozen, not quite frozen pools of water. And so I said, “Okay.” I just dove into this giant puddle of probably 35-degree water, not quite ice. And they laughed and laughed and laughed and they all laid down in this muddy swampy bog to send this message about the arctic and a giant form of Caribou.

So that renewal of our epic nature, which is a combination of the childlike wonder that we have for this experience called life and that people are stronger than they really understand. They’ve been living in a society with guardrails and safety belts. My artwork tends to push people to the edge of their comfort zone. We try to make it as fun as possible but at the same time I think it’s good for people to go… and then usually the great forgiver is when they see the images and they’re like, “Whoa. We did that together,” and then it becomes a real point of pride. I think I’m a big fan of people going to their edge. I think that makes for more dynamic, more fully alive humans, and when people are activated in that way they make better decisions. They have a richer life experience. There’s less conflict.

The more people who step into this place of being creatively activated while firmly rooted in nature, I just think good things will come from that. That’s where the solutions will come from.

Monica: The way that you do your art has an opportunity, in each of these ephemeral installations, to touch hundreds, even thousands, of people. And the title of this particular Turtle Talk is “Does Humanity Evolve?” So I wonder if you might have a reflection on that, how your work might be possibly evolving humanity?

John: Well, I think that we are evolving into a greater awareness of our oneness. In a sense what we do with these human aerial art projects is we create a larger sense of oneness in the moment. So one person becomes a thousand people, becomes a giant whale. And with kids I see this a lot. And there’s a really interesting moment that occurs in almost all of these images where at first people are just sitting in a spot, they don’t really understand what’s happening and then there’s a moment, we were doing a piece on Bondi Beach in Australia many years ago and you could see it. You look around and people are wrestling around and moving their bags. I’m always thinking from an artistic and precision standpoint of I need them to be in certain spots for it to work because if they’re not, then it’s not the drawing that we set out to do.

I’m looking around and we had this wonderful aboriginal gentleman named Bunna with his didgeridoo who literally went and didged all 2000 people in this whale. And as he was walking down the lines blowing his didge, playing his didge, there was this moment where you literally… I could feel it on my shoulders and my back those chills, and I looked around and suddenly everyone had become a giant humpback whale. There was no more fidgeting, there was no more moving, everyone was in their spot. And it was like the group mind, the group experience had taken over. There’s almost always a moment like that in these, where it goes from the individualized experience to the sense of the one thing that we’re all doing. I think in that moment. They have demonstrated and we have demonstrated that it’s possible for that moment to self-identify as something larger, as part of something larger than ourselves. When we have that group “aha” as a world, then human activities are going to shift profoundly.

Ultimately, the more experiences we have like that, the more in sync we are as humans. If we were to just refocus all of our energy, lifting up everyone so that we all have the basic necessities and things like that, what is possible with this world? I mean it’s incredible. It’s incredible. It’s just really about redirecting our focus and attention.

The more people whose brains, whose hearts, whose spirits and souls are resonating and emanating the possibility of a world, of a collaborative, cooperative, creatively dynamic world the better chance we have. My mission is to activate and create the opportunity for activation for as many people as possible.

It requires a certain amount of letting go of the outcome, just keep the spark going, keep the spark going.

Every once in a while, read the score card of how you’re doing, but if you become addicted to reading the score card, chances are you’re going to fall into a depression. It’s just read the score card in your heart. Are you doing every day what you feel is the most powerful, passionate thing to make the world a better place? Does it make you come fully alive? And that’s the score card.

Monica: What does that feel like for you?

John: Am I putting my energy into things that make the world a better place for others as well as me? Recently I was thinking about the difference between the “me dream” and the “we dream”. You’ve probably heard this phrase before. But most of us when we’re coming of age we have a “me dream” like what I want to do with my life, what I want to be, how successful I want to be. And then there’s a certain moment where you start to realize the more refined higher evolution of that is what can we create together? I have my individual part but what can we create together? So for me every day the question I ask myself is “Am I using all of my talents to move the world towards a better place?” Who I’m working for are future generations. That’s who I’m working for.

And fortunately I’m having a great time along the way and I think that’s really key. Are you having fun? Because I think there are a couple of different parts to it. One is celebrating the beauty along the way. Because if all you are is trying to change what’s here and you’re not recognizing how much beauty is already here, that doesn’t necessarily do any good either. So celebrate the beauty every step of the way, the proverbial take time to smell the flowers, smell the roses, that sort of thing. And then the other is there are so many things going on in the world that need to be changed — injustices where people are suffering from violence and discrimination and where the earth is being destroyed at a rapid pace. Find a way to activate yourself into those situations.

Monica: If you project forward and you’re looking back over your life, what is it that you want to see? What would be your legacy?

John: It’s funny. I like to live life with a twist in the sense that I’m a wild spirit. I like to say that wild horses still exist, and I like to consider myself one. I guess for me that I didn’t buy in to conventional wisdom and that I just relentlessly pursued a vision of a world that exhibits a tremendous amount of love in it. And love in the sense that, not just the feeling of love but love is when people have equal rights. Love is when injustices are made right. Love is when the economics of our world are being played in a way that is fair for everyone. It’s not just the thought or the feeling of love; it’s “Is the world being run and operated in a way that expresses what love really is?”

For me, I want to be someone who never wavered from those ideals. One of my favorite quotes I heard early in my activist career was “The only true aging is the erosion of our ideals.” So I want to have stayed true to that. And as I get older I understand how easy it is to fall into either the trappings of comfort or into a more fear based reality because you start to become more vulnerable. You’re tired. You’ve been doing it for decades but my torch that I want to hold aloft is the possibility of living out my days always staying true to those principles that this world of… I love that song “Imagine”. That’s kind of a guiding light, that it’s possible. And that the more of us who don’t do it for a decade or a couple of years and then go “Well, we tried and then we gave up,” for me, it’s like I stayed true, I stayed strong and I just kept going and had an amazing adventure along the way. That’s really key for me. I love adventures. I love going to wild places so I’ve built that into my life plan. Life is an adventure. Just grab it, enjoy it, and hopefully help people along the way.

There’s one other thing on that actually. We’re in the process of a transition from the industrial age to what we hope will be the sustainable renewable age. I see it coming and I’ve been working on it for a couple of decades, and that is one thing 20, 30, 40 years from now I’d like to look back and go “Wow, that was rough.” There were some close calls there but as a species, as a society, we were actually able to navigate transitioning how we operate. I would love to look back and go, “Wow. All those decades of work finally paid off and it’s a whole new world now.” That would feel awesome.

Monica: It’s an exciting time to be on the planet.

John: Yeah.

Monica: With a big transition like that.

John: Yeah.

Monica: It’s not really for the faint of heart.

John: No, and there are a lot of forces who want us to just curl up and go into our little cubicle, put our headphones on and live in our little world of consuming entertainment and all of that. And that’s why I so value the wild spirit. I encourage everyone to get arrested at least once in your life for something that you believe in. That singular experience as a rite of passage will do more for you than just about anything you’ll experience in your life because it will push you past all of your fears or at least many of them and you will be stronger for it. That’s my recipe. Risk yourself politically. Risk yourself physically. Push yourself to an edge where you actually feel what that is to be right on the brink. I’m not talking about going out being stupid and doing something that is just a bad risk, but in a situation where there’s rock climbing or something where you feel fully alive.

Activate your deepest dreams. Good things will come. I’m a big proponent of risk. Basically the best things that I’ve done in my life require me to risk my life; very literally, physically. But risk comes in many forms. Risk is the sort of life blood of reaching our potential and catalyzing transformation, getting out of our comfort zone. And so anyone who’s listening to this right now, if you were to think about… just close your eyes and just think about for a moment “What am I afraid of?” There are several thoughts that would come immediately that you would put out of your head, no, no I’m not afraid of that. But you know what it is, there are things that are knocking on your door that you always wanted to do but were afraid to do, or things that really you don’t want to have to face but every time you face one of those you expand as a being. And if it’s not enough that that helps you, just know that it helps the world.

I encourage you to risk, face your fears, extend yourself beyond where you are right now, and from there you will set off a chain of events that will lead you to a radically new place. I can pretty much guarantee you that that radically new place is going to be a better place than where you are now.

Just be present with the edges of our being and as you do that, your life will ignite. We need more wild horses.

Monica: John, thank you so much for sharing your life experiences and perspectives with us. It’s really inspiring.

John: Thank you. Thank you. It was beautiful to be here.

Turtle Talks | Episode #12: What Will Be Your Legacy? - Turtle Talks

Posted at 16:00h, 29 March[…] John Quigley, aerial artist and activist whose iconic human installations deliver powerful, large-scale messages for the common good […]